A pilot details her return to the high-country skies.

You could respond with a simple answer, or you could dive in more philosophically. Given that the registration form also noted that we would be formulating Life Flight plans, the intention with the question was clearly broader than simply probing our need to improve our confined-airstrip-landing skills.

Weather in Cascade in the third week of September can offer up anything from summer-like temps and density-altitude concerns to drizzly clouds and mountain-obscuring ceilings—or even a blizzard. I scheduled two days of instruction according to the forecast, knowing I could add an aerobatic flight or some tailwheel practice as the actual conditions allowed.

To balance the flying time, Tindle scheduled briefings from the instructor corps in the afternoons and evenings. For example, in one evening, Bob Del Valle of Hallo Flight Training (based in Priest River, Idaho) covered key concepts, such as engine failure after takeoff and accelerated stalls, as well as decision-making skills tuned to the environment in which we’d fly.

I spent my first day of flying with Fred Williams, an instructor who splits his time between Cascade and Reno, Nevada. He offered up his Kitfox with large-format tires for our flying—an airplane I’d flown only briefly with a friend in the more urbane environs of airpark-rich Florida.

Once briefed, we launched into blue and headed east to the practice area, in the valley hosting the Landmark, Idaho, airstrip (0U0). Before reaching the airport vicinity, Williams had me practice canyon turns in the broad valley, slowing down bit by bit to tighten them up. A canyon turn takes advantage of the fact that reducing your airspeed decreases the radius of your turn. If you execute a turn using a 30-degree bank at a near-cruise, density-altitude-adjusted groundspeed of 120 knots, the radius of your turn is 2,215 feet. At a speed near VA for many single-engine airplanes—say, 90 knots—you take up a lot less real estate, at 1,246 feet. If you can safely reduce your speed to 60 knots, that figure drops to 553 feet, and you can just about execute a 180-degree turn in 1,100 feet laterally. Use of flaps can help maintain a slower speed—making a huge difference when you contemplate a course reversal below canyon walls.

But those take practice to execute well. In Del Valle’s briefing, he had gone over the increased stall speed inherent with a turn of increased bank. With a bank angle of zero, let’s say your airplane has a stall speed (VS) of 60 knots. At 30 degrees of bank, that speed increases 10 percent to 66 knots; at 45 degrees of bank, it’s up to 72 knots. Because the Kitfox’s VS was much lower than 60 knots—try 49 mph with no flaps—we had a lot of room to play with, but still the smaller the bank, the less the chance we’d run into accelerated-stall territory. A good canyon turn is a balance of these aspects.

Surveying the strip—what some pilots call “shopping,” a term I first heard from MacNichol 15 years ago and in common usage among Idaho pilots—takes practice, too. Flying an extra traffic pattern gives you time to ferret out the details. Sometimes, you have to do this a lot higher than a standard traffic-pattern altitude, and you might not have sight of the strip during the approach until you’re on short final.

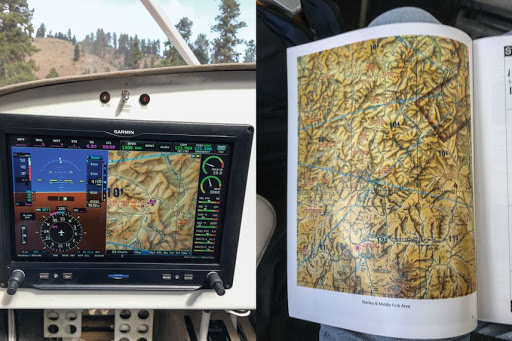

At Landmark, we had a relatively wide-open valley in which to maneuver as we gauged the status of its 4,000-foot-long, 100-foot-wide surface. As we worked through the day, flying to Indian Creek (S81) and Thomas Creek (2U8), we would need progressively more-inventive ways to survey the landing site before making our approach. On day two in the 182, we would do the same with instructor Stacey Burdell, scoping the scene at Stanley (2U7), Smiley Creek (U87), Idaho City (U98) and Garden Valley (U88), consecutively.

Checking the actual weather against the forecast also proved most important, especially because of the winds at ridge-top level contradicting those at the surface—or even at the ends of the same runway. With Williams on day one, I shopped the strip at Mahoney Creek (0U3) only to see its windsocks voting in opposite directions. As much as I wanted to land there and tag another new strip in my logbook, we left it for another day. We bounced around enough on the way back to Cascade (U70) to validate my choice.

If you have this image of a backcountry pilot making crazy maneuvers to “make it” to a landing, dispel them from your mind right now. If you have any sense, you won’t accept anything less than a stabilized approach—and you’ll bail out early if you can’t maintain your airspeed and sight picture.

That said, the stabilized approach to a backcountry strip looks a little different than the one you might use in normal ops. This stems directly from the fact many mountain strips are one-way-in runways and have a “point of no return,” after which you must make the landing. A super-low-speed, power-off, short-field approach doesn’t offer the same margins for adjustment at the last minute that the backcountry approach does.

We practiced at Landmark—which has no point of no return because of its position in the valley—setting up a steep, low-power descent at a moderate rate, with full flaps in the Kitfox (think 30 degrees if you were flying a Cessna 172) and a speed at 1.2 to 1.3 times VSO, which correlates to about 55 mph indicated in the Kitfox. This configuration offers the ability to use more or less power if needed and modify the descent rate to avoid landing short—or long.

The key is to lock this in well before you reach your predetermined go-around point. If you don’t have the configuration in place and stable, you need to execute the go-around before that point of no return, or you risk everything. One of the approaches on day two was not well-stabilized, at Garden City, and it drove home the necessity of staying diligent about this practice—and being locked and loaded to go around if you’re too high and too fast at the key position, rather than forcing the approach.

There’s an aspect of facing and conquering the unknown that carries over into the rest of your experience. The mountains are personal to me, and returning to them at a perfect time in my life, when I needed a shot of self-confidence, made all the difference in the world.

As weather drew in on day three, we bagged the airport activities for a hike into a nearby hot springs as the snow fell around us. The camaraderie was real as we navigated slippery rocks, and it would continue on in the aviation friendships I made that week. Our Plan B was just fine—and executing it reiterated the joy of taking advantage of life’s sharp turns. A disappointment became an opportunity to enjoy the natural beauty of a place we could access through general aviation. That’s another lesson that feels particularly poignant now as we face uncertainties ahead in life.

On the last evening of the seminar, the group encapsulated our plans for the coming days, weeks and months into concrete goals. Mine was simple: to keep flying. To keep exploring new places only an airplane can reach. To tap into that well of confidence-building stuff that only learning to fly has provided me. And that too is something every pilot can take away.

- Pay attention to micrometeorology—and understand how fast the weather can change. In both the mountains and the lowlands, the environment immediately surrounding an airport can funnel winds and generate up- and downdrafts worthy of note, along with localized clouds and reduced visibility.

- A stabilized approach is a safe approach. While you might use a different technique for your approach to a “normal” runway, setting a configuration and rate of descent to have in place by the time you’re at 500 feet agl—or higher—will stack the deck in your favor for a better landing.

- Practice and plan for a go-around every time. In the backcountry, your go-around decision point might not be over the runway, or even on short final. Committing to a go-around plan, and knowing when you’ll trigger it, is vital. This holds true with every single landing you attempt.

- The go/no-go decision continues throughout the flight. While you may consider the flight launched once you’re airborne, you’re always in a position to return to the place you just left, divert, or come up with some alternative to the plan you had in mind. This mental flexibility may very well save your life someday.

- Take the right equipment. Save room (and weight) for a well-stocked flight bag—one that holds an extra layer of clothing, a hat, a first-aid kit, food and water, and other emergency supplies. Landing out, even in the flatlands, can leave you far from assistance.

Two books guided my research, and a host of content online supports the topics they cover.

If there’s a primary textbook for flying in the high country, Mountain, Canyon, and Backcountry Flying by Amy L. Hoover and R.K. “Dick” Williams is it. Hoover has been flying the Idaho backcountry since 1989 and started teaching mountain flying in 1992 while working as a backcountry air-taxi pilot. She’s an original co-founder of McCall Mountain Canyon Flying Seminars. For the book she teamed up with pilot legend and author Dick Williams, who started training pilots in the backcountry in 1985. It’s available through Aviation Supplies and Academics.

For those who want their mountain flying in concise form, seek out a copy of Mountain Flying by Sparky Imeson, published in 1987 by Airguide Publications. Imeson, who ironically died in a March 2009 accident involving his Cessna 180 in the mountains, founded Imeson Aviation in 1968 at the Jackson Hole Airport in Wyoming. His wisdom—and the website, mountainflying.com—lives on, disseminating his vast knowledge of the techniques and decision-making critical to flying safely in the backcountry.

Tindle plans more WomanWise Aviation Adventures for 2020, though at press time they remain in flux because of general travel concerns in the spring, which we all hope to have dissipate by summer. Tindle said in March, “[I’m planning] September 6 to 10 in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, for high-mountain flying, aerobatics and spin [training], and soaring, which is new. [Then it’s] October 25 to 29 in Moab, Utah, for backcountry flying, aerobatics and spin [training], and ballooning—also new.”

Check womanwiseaviationadventures.com for more details.

Also, look to Fred Williams’ Adventure Flying LLC for the wide range of flight training he provides in Cascade, Idaho, and Reno, Nevada, both in the Kitfox or in the aircraft you bring (contact Williams for details via advflying.com). Bob Del Valle offers instruction in Sandpoint, Idaho, as well as around Montana and Washington (halloflighttraining.com). Sam Davis offers instruction in aerobatics, as well as upset prevention and recovery, in the Heber City, Utah, area through Pilot Makers Advanced Flight Academy (pilotmakers.com).

No comments:

Post a Comment